Cameroon’s richest man, Baba Ahmadou Danpullo, is set to pocket a slice of Sodecoton’s 500 million CFA francs ($810,000) dividend after shareholders of the state-controlled cotton company approved a 2024 payout, even as Yaoundé consolidates ownership of the agribusiness linchpin.

The dividend—about 9% of last year’s net profit—underscores a conservative stance as the company fortifies its balance sheet and shrugs off a choppy input-cost cycle.

It also lands months after the government lifted its stake in Sodecoton to roughly 89% by buying the 30% block previously held by France’s Geocoton for about 46 billion CFA francs, part of a broader reset of the company’s shareholder base. Local press tracking the transaction says producer groups now hold around 12%, staff own a small sliver, and Danpullo’s Société Mobilière d’Investissement du Cameroun (SMIC) remains at 11%.

For Danpullo, the dividend is small change next to a portfolio that runs from tea and ranching to telecoms and South African real estate. Through his holding companies he controls Cameroon Tea Estates and the Ndawara Highland Tea Estate, operates large ranches, and has long been a significant shareholder in Nexttel, Cameroon’s No. 3 mobile operator. He also built one of South Africa’s biggest privately owned commercial-property stables, including Johannesburg’s Marble Towers.

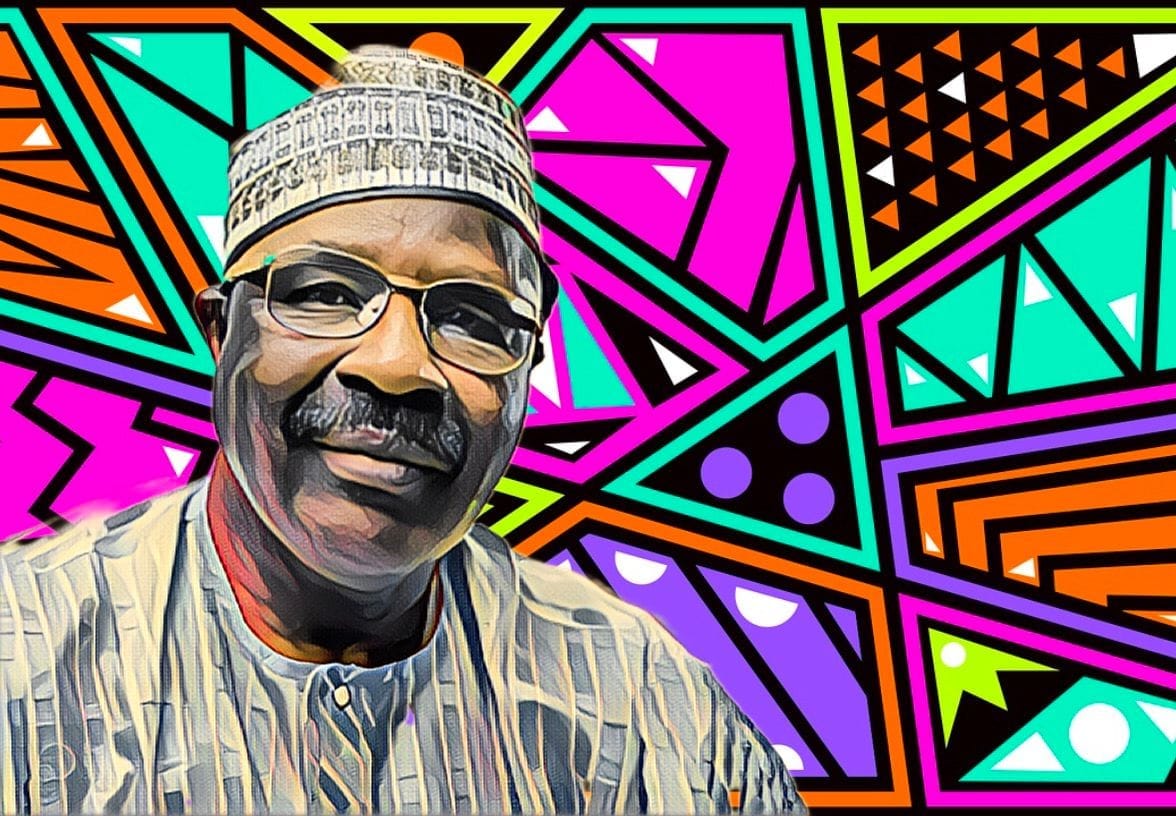

The 74-year-old magnate—who has topped wealth rankings in Cameroon for years—has kept a low public profile while routinely surfacing in sectors that matter to the economy: cash crops, logistics, finance and phone networks. Billionaires.Africa pegs his fortune at roughly a billion dollars in recent years, a figure built on diversified cash flows and often-contrarian bets.

Not everything has run smoothly. Danpullo’s South African banking dispute with FirstRand’s FNB spilled into cross-border legal wrangling over seized assets and, briefly, tensions involving MTN’s local accounts—an episode that underlined his political reach at home and the risks of operating abroad.

Back at Sodecoton, the state’s heavier hand is part of a push to ring-fence a strategic value chain that supports hundreds of thousands of livelihoods in Cameroon’s north. Brussels-backed modernization plans with AFD and the EU, paired with a chastened capital policy, suggest the company will keep prioritizing factory upgrades, ginning efficiency and farmer support schemes over richer near-term shareholder rewards. For minority holders like SMIC, that likely means steady—if unspectacular—cash returns as the state steers for stability.

Crédito: Link de origem

Comments are closed.