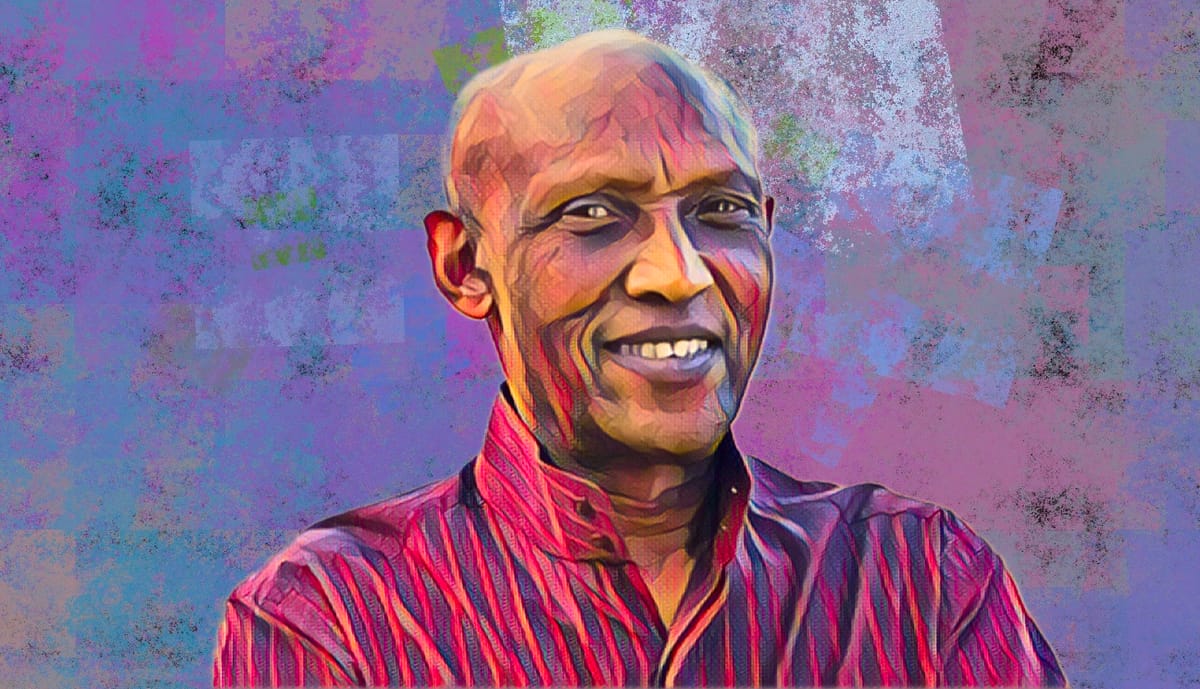

On the night of April 16, 2024, Tribert Rujugiro Ayabatwa — Rwanda’s most polarizing industrialist and for decades one of Africa’s most formidable tobacco magnates — died at home in Dubai. He was 82. The obituaries were brisk. What he left behind is a pan-African commercial labyrinth of factories and trading companies, a legacy of bruising political fallouts, and a succession plan that — by design or necessity — operates behind smoked glass.

Born in Rwanda around 1941, Ayabatwa fled to Burundi as a young man, taught himself the art of commerce across hostile borders, and by the late 1970s was manufacturing cigarettes. From those early plants in Burundi and Zaire, he built the Pan African Tobacco Group (PTG), a private conglomerate with manufacturing roots in Angola, Burundi, DR Congo, Nigeria, South Sudan, Tanzania and Uganda, with a historic trade reach into the Gulf. His signature brand was Supermatch, and the corporate structure was a thicket of local subsidiaries: Leaf Tobacco & Commodities (Uganda and Nigeria), Barco Trading (Angola), Congo Tobacco Company, Burundi Tobacco Company, Mastermind Tobacco in Tanzania, and Vision Tobacco in the UAE.

A political fallout with Kigali

For 15 years after the 1994 genocide, Ayabatwa was a pillar of Rwanda’s business revival — an adviser to President Paul Kagame, a chamber of commerce heavyweight, and a key private investor. Then came the break. Kigali accused him of tax crimes and political subversion. He called it a political vendetta. In 2010, he left Rwanda and never returned.

In 2013, the state seized the Union Trade Centre, his $20 million Kigali mall, calling it an abandoned property. He fought the seizure through the East African Court of Justice and won in 2020 and again on appeal in 2022. But the property was never returned — the remedy was financial damages. The episode marked a public rupture between Kagame and the businessman who once helped bankroll Rwanda’s postwar economic resurgence.

The fallout had regional consequences. Kigali pressured Uganda to push him out of the country, but Kampala refused. Tensions boiled over into a diplomatic freeze between Kagame and Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni, including the closure of the Katuna border in 2019. The chill lasted years, with tobacco shipments and ordinary cross-border trade caught in the crossfire. Yet PTG’s Meridian Tobacco plant in Arua kept running — a quiet show of strength in the face of geopolitical storms.

The hidden heirs

PTG has no public annual reports or shareholding disclosures. The only glimpse into its leadership came in 2013, when the founder announced his retirement. He named his eldest son, Paul Nkwaya, as marketing director; his youngest son, Richard Rujugiro, as technical director; and his son-in-law, Serge Huggenberger, as financial director. He would remain an adviser.

A decade later, those names still surface in industry whispers but rarely in print. The family maintains a near-total media blackout. There are no public appearances, no corporate interviews, and almost no digital footprint. For a company that moves product in multiple jurisdictions, invisibility is not a glitch — it’s a strategy.

Scandals and smuggling shadows

PTG’s flagship brand, Supermatch, has been mentioned in numerous reports on East Africa’s illicit cigarette trade. Law enforcement records and investigative reporting have tied smuggling networks to shipments of the brand — often moving through porous borders into Uganda and South Sudan. To be clear, illicit trade in East Africa predates PTG and touches every major brand in the region, but Supermatch has been a consistent presence in enforcement stories. PTG entities have also spent years defending their trademarks against counterfeit and gray-market operators.

Nigeria has also been a contested arena. While British American Tobacco has dominated headlines for regulatory fines, PTG’s Leaf Tobacco & Commodities (Nigeria) has operated mostly in the shadows — away from the public spotlight. In an industry where regulators and giants wage open war, smaller players often survive by saying less.

Reputation in a contested industry

PTG publicly frames itself as a pan-African manufacturer rooted in local economies — creating jobs, buying local leaf, funding community projects. But activists and policy experts see a different picture: allegations of smuggling, claims of political shielding, and concerns about the ethics of operating in weakly regulated markets. The truth sits in the gray zone. Illicit cigarette flows in East Africa are structural, not singular. Any company operating at scale in that environment risks being implicated — or at least entangled — in its undercurrents.

Why the Secrecy?

Opacity was a survival instinct for Ayabatwa. He was jailed and expropriated in Burundi in the 1980s, exiled from Rwanda in 2010, and saw a major asset seized and auctioned by the Rwandan state. He became a pawn in a mini–Cold War between Kigali and Kampala. In that context, transparency isn’t just bad for business — it’s dangerous.

PTG remains a network of national entities in politically volatile environments. It’s not listed on any stock exchange. It has no obligation to issue financial statements or leadership announcements. Succession is a family affair. Silence, in their calculus, is security.

The empire after Ayabatwa

Today, PTG continues to operate in at least seven countries. Its UAE arm, Vision Tobacco, remains a key manufacturing hub. The 2013 succession plan — placing Paul Nkwaya, Richard Rujugiro, and Serge Huggenberger at the helm — appears to have endured, even if unofficially. None of them has publicly claimed the mantle of CEO. The company seems content to remain what it has always been: profitable, political, and almost invisible.

Crédito: Link de origem

Comments are closed.